(845) 246-6944

· info@ArtTimesJournal.com

By FRANK BEHRENS

ART TIMES June 2007

|

Of

the now countless video offerings

of operas, most are “live” performances while an increasing number are

made in a studio, usually with lip-synching. As each has an advantage

over the other, I would like to give a few examples.

A

video of a performance given before an audience means pretty much that

you see what the audience saw, except for the close-ups and occasional

camera effects that the audience could not have seen. You see the orchestra

before each act, you hear the applause to greet them and to reward the

singers after an aria or ensemble, and (in short) you share the experience

with the audience.

Or

do you? You are at home watching this video. You have no contact with

that audience. In fact, they are part of the show, as it were, in dress

and demeanor acting to no less a degree than the singers on stage. In

a way, you are more aware of the production as a social event. Might

one suggest a ritual?

Now,

when watching a film you MIGHT think of the cameramen, the script person,

the director, and all the crew that are not seen on the screen. You

simply let yourself believe that Laurence Olivier IS Hamlet or Richard

III, and you believe that all of this is “really” happening.

Here

is a good case in point. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, 13 operas

were filmed to be shown on German television. This was because of Rolf

Liebermann, who built the Hamburg State Opera into a formidable organization.

After a tour of North America, the film and TV company Polyphon decided

to telecast versions of those operas based on productions already performed

on stage in Hamburg. Joachim Hess was chosen to do the film adaptations.

The

telecasts were a great success and have languished in vaults until quite

recently when ArtHaus Musik was given the rights to make some of the

films available on DVDs. The earlier films show some unfamiliarity with

the art of lip-synching. That skill was quickly mastered and the later

films seem to be done “live.”

The

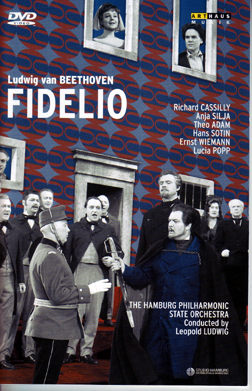

later releases so far include Lortzing’s “Zar und Zimmerman,” Beethoven’s

“Fidelio,” Von Weber’s “Der Freischutz,” Berg’s “Wozzeck,” Penderecki’s

“Die Teufel von Loudun,” and Wagner’s “Die Meistersinger.” More might

have been added by the time this essay is printed.

Now

for some comparisons.

I

will take two videos of “Meistersinger” as an example. There is the

spectacular version performed at the Metropolitan Opera in 2001. Here

we have realistic sets, costumes appropriate to the time and place of

the action, and a good cast. Ignoring the fact that the young Eva looked

far too matronly in close-ups, it was an impressive production that

left me somewhat uninvolved with the characters. I have never found

this work particularly exciting once the overture is over and I look

forward to the riot scene that ends Act II and the procession of the

guilds in Act III.

Not

too long after viewing that Deutsche Grammophon video, I saw the ArtHaus

DVD. Here was a color studio-made version from 1970. Although the tenor

was not exactly attractive and something of a wooden actor, I found

myself very IN-volved indeed. Perhaps the acting was a bit more natural,

perhaps the proximity of the camera let the cast ease up on projecting

emotion to the top balconies. I don’t know. I simply feel I would like

to see this version again in its entirety and the Met version only in

parts.

The

1968 “Fidelio” from Hamburg is sensibly costumed in the correct period

and is far more effective than the updated

costumes and settings offered in the Metropolitan Opera performance

released on video in 2002; and again I find myself more in sympathy

with the characters and their problems.

On

the other hand, the film version of “Der Teufel von Loudon” contains

far too much nudity and sadism to show on a stage. The latter is so

realistically graphic that I had to stop watching it towards the end.

There

is, of course, one major disadvantage to studio-made operas. Liebermann

himself is quoted in the program notes to “Fidelio” pointing out that

he realized after filming 6 of the 13 operas that “miming falsifies

a singer’s facial expressions. A high B or C doesn’t ring true if the

singer has a completely relaxed expression.” Indeed, in some operatic

films non-singing actors are used to mouth the voices of less attractive

opera singers. (Do you remember Sophia Loren as Aida?)

Another

problem with films shows up in the “Wozzeck” video. The action is certainly

earthy and the sets are “on location,” both of which features make it

awkward to have the characters singing rather than speaking.

In

sum, I have to conclude that there is a place for both “live” and studio-made

videos—as long as they are intelligently directed by people who

respect the work and do not want to build a reputation merely by outrageous

settings and costumes.